Colorectal Cancer

Let’s talk about cancer.

We all spend a lot of time thinking about diet for many things – diabetes, weight loss, hypertension, heart disease – but the fact is a great diet offers as much protection from cancers as it does from the usual suspects of cardiometabolic risk.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is, quite simply, cancer of the colon and rectum and is one of the leading causes of cancer mortality. Forty percent of those who develop colorectal cancer will die of the disease.

Most of colon and rectal cancers are believed to arise from transformation of one of three types of colon polyps: adenomatous, villous adenoma, or serrated. However, through regular screening, precancerous polyps can be found to catch it in the earliest stages. While approximately 75% of all cases occur in those with no known predisposing factors, we have identified numerous risk factors that contribute to the chances of developing colorectal cancer. 1

The main contributors of increased risk are family history, age, body weight, physical fitness, and diet. Current statistics show that 20% of CRC patients have a family history of the disease, 90% of cases occur in those over the age of 50 years, those with a BMI greater than 40 have a 45% higher risk, and physical activity of at least 4 hours per week cuts risk in half. 2,3

Dietary Effects on the Risk of CRC

Multiple studies have shown a direct correlation between the development of colorectal cancer and diet. Recent research on the DASH (Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension) diet, for example, found a 20% reduction in the risk of CRC among more than 130,000 study participants. 4

Saturated Fat and Animal Fat

There is strong evidence that less animal fat in the diet is associated with lower rates of colon cancer. 5,6 One possible explanation is that saturated fats modify how bile is handled in the body (bile is produced by the liver, stored in the gall bladder, and helps us absorb fats). This appears to alter gut flora (the good bacteria that live in our guts) toward a more cancerous microenvironment. White meat, like chicken, is not associated with a higher risk of colorectal cancer, however. This may be because one of the main differences between red and white meat is the iron content. 7

Heterocyclic Amines

Heating red meat chemically alters the proteins it contains and can convert them to cancer-causing agents. Several studies have found that the risk of colon cancer is increased among people who consume more meat that has been prepared at high temperatures, for a longer time, or with blackened surfaces. When meat is cooked, a substance known as “heterocyclic amines” are formed from creatinine, a waste substance that is generated from metabolizing meat. The heterocyclic amines further interact with amino acids in a way that increases the rate of changes in the cells of the colon, and it is these uncontrolled cellular changes that can become cancer. In the Harvard School of Public Health’s Health Professional Follow-Up Study, consuming more of the heterocyclic amines formed during cooking was associated with adenoma (a non-cancerous tumor that may become cancerous) of the lower (distal) colon, regardless of total overall meat intake.

Further studies examining interactions between meat intake, cooking methods, and genetic variations that affect the metabolism of heterocyclic amines also provide strong support for the existence of a link between these carcinogens and abnormal colorectal growths. 8

Most, but not all studies that look at alternative sources of animal protein, including low-fat dairy products, fish, and poultry, have shown them to be associated with a lower risk of colon cancer compared with consuming red meat. 9

Fiber

Higher fiber intake is associated with a decreased risk of CRC. Insoluble fiber, which is well known to increase stool bulk and help the stool move through the colon more quickly, may dilute toxins and reduce the amount of time the colon’s lining is exposed to carcinogens 10, while also reducing secondary bile acid concentration in the intestines and colon. 11 Good sources of whole grain fiber include rye breads, whole grain breads, oatmeal, whole grain cereals, high fiber cereals, brown rice, and porridge. 12,13

There is little strong evidence of an association between intake of fruit, vegetable, or legume fiber alone and reduced risk of colorectal cancer, however. 14 That said, fiber has been demonstrated to reduce DNA damage in healthy volunteers as well as CRC patients.

Folate and B6

A higher intake of folate and B6 similarly decreases your risk of CRC, as folate and B6 both contribute to the methylation of DNA. The methylation of DNA helps suppress tumor creation and reduced cell proliferation as well as helping to relieve oxidative stress and reducing the creation of new blood vessels that tumors need to grow. A few excellent sources of folate and B6 include leafy greens, beans, whole grains, and colorful vegetables. 15

Calcium and Vitamin D

Those with elevated calcium and vitamin D intake were also seen to have a lower risk of colorectal cancer and fewer benign colon tumors in several studies. Calcium ultimately affects cell reproduction, differentiation, and natural cellular death. Additionally, it binds and alters the structure of bile acids, decreasing the acid’s ability to destroy cells. Sources of calcium include milk, yogurt, cheese, soybeans, broccoli, and almonds. 16

Refined Starches

Starches and sucrose may also play a role in cancer development with the involvement of bioactive IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) and insulin receptors. Studies have shown that those consuming the most refined carbohydrates (sucrose, refined starches) are twice as likely to develop colorectal cancers than those who eat the least refined carbohydrates. 17

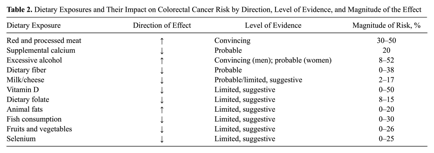

Summary of Recommendations 18

This table from an article by Vargas, et al sums up the impact of specific dietary patterns on colorectal cancer.

1. Cancer Res July 1, 2013 73; 4020

2. Cornett P.A., Dea T.O. (2015). Cancer. In Papadakis M.A., McPhee S.J., Rabow M.W. (Eds), Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment 2015. Retrieved October 10, 2014

4. Vargas AJ, Thompson PA. Diet and Nutrient Factors in Colorectal Cancer Risk. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2012;27(5):613-623. doi:10.1177/0884533612454885.

5. Chao, A. et al. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer. JAMA 293, 172-182 (2005).

6. Nutr Clin Pract October 2012 vol. 27 no. 5 613-623

7. Cancer research 2010; 70(6):2406-2414.

8. Gastroenterology 2009; 138(6):2029-2043.e10

9. Gastroenterology 2009; 138(6):2029-2043.e10

10. Ou, J., DeLany, J. P., Zhang, M., Sharma, S., & O’Keefe, S. J. (2012). Association between low colonic short-chain fatty acids and high bile acids in high colon cancer risk populations. Nutrition and cancer, 64(1), 34-40.

11. Nutrition and Aging 2014; 2(1):45-67.

12. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:1754-64

13. Aune D et al. BMJ 2011;343:bmj.d6617

14. Aune D et al. BMJ 2011;343:bmj.d6617

15. Le Marchand L, White KK, Nomura AMY, et al. Plasma Levels of B Vitamins and Colorectal Cancer Risk: The Multiethnic Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(8):2195-2201. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0141.

16. Nature Reviews Cancer 2007; 7:684-700

17. Gastroenterology 2009; 138(6):2029-2043.e10

18. Vargas AJ, Thompson PA. Diet and Nutrient Factors in Colorectal Cancer Risk. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2012;27(5):613-623. doi:10.1177/0884533612454885.